Memphis, Tennessee is my hometown. It’s also the hunger capital of the United States.

Part of what makes Memphis the food capital of America, is the fact that the city is rich with food deserts, or areas that are not within close proximity of supermarkets or grocery stores that provide fresh, quality food. Access to transportation to supermarkets is limited in food deserts as well. Whether it be owning a car and/or being able to use public transit with little to no hassle.

I attend a small school situated in a section of town called “Midtown”. Midtown is located east of downtown Memphis, and CBU in particular, is across the street from the city’s largest sports venue, the Liberty Bowl, and is sandwiched in between two major roads that lead to downtown.

As an undergrad, I’ve had a few all nighters (some more scholarly than others). Walmart, the largest food retailer in the country, is open 24 hours (pre-COVID) and is always a viable option for a late night snack. The closest Walmart is not a supercenter, but is a Neighborhood Walmart that isn’t open around the clock. It’s also 11 miles away. The closest Walmart supercenter to CBU is about 8 miles away, at least a 15 minute drive without any traffic. If you’re a CBU student that wants to grab some food from a grocery during late hours and have no means of transportation, then you’re out of luck (unless you don’t mind a vending machine). And we’re talking about a privileged college student that attends an institution that costs around $44k a year to attend. Imagine someone who doesn’t have nearly the amount of resources a CBU student has to potentially finagle their way to the nearest Walmart or grocery store in general.

Ironically, CBU’s campus is not within a food desert. There’s a Fresh Market less than a mile away. The next closest grocery stores are a Cash Saver, and two Krogers. Each are at least 2 miles away from campus. I say this to put things into perspective by exactly how sparse quality grocery stores are in Memphis.

CBU is within the “38104” zip code, which encompasses all of Midtown. The zip code itself is not considered a food desert, but to say the least, as mentioned before, the pickings are somewhat slim. If we take a closer look at the 38104 zip code, the median household income is $41,696 which is about on par with the city’s average of $41,228. Zip codes with average median incomes that are much higher than the city’s average, have more options than the averagely affluent Midtown area (an area many Memphians perceive as “bougie”).

A short drive eastbound on Walnut Grove leads to the most affluent zip code in the city, 38120, or East Memphis. The median household income is $99,472, and 20% of the households in the zip code earn over $200k a year. The amount of grocery options in the zip code positively correlates with the median household income.

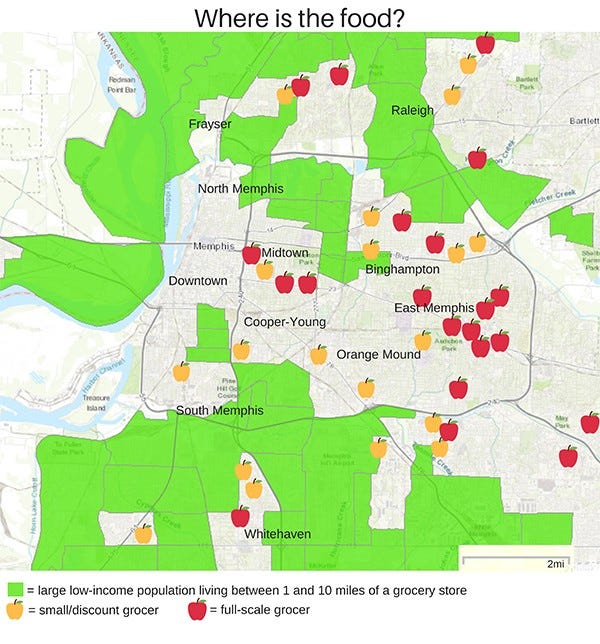

Peep the amount of apples in the Midtown area compared to East Memphis. And how scattered they are throughout the city. In terms of wealth, Midtown is average compared to the rest of the city.

All of the green on the map represent food deserts. What it doesn’t state, is that it represents the poorest and unhealthiest zip codes within the city too. Dr. Elena Delevaga from the University of Memphis’s School of Social Work releases the Memphis Poverty Fact Sheet annually. The collection of data has been a go to resource for me (and I’m sure many others) and is worth reading every year. Delavega and the School of Social Work do a magnificent job of capturing data that represents poverty’s intersection with other problems in the Memphis metro area.

Some of this data includes demographic breakdowns of poverty in the city, and each zip code within it. The maps provide a clear representation of that (including the one pictured above). In 2018, the Shelby County Health Department found that the zip code of Shelby County and Memphis residents essentially determines one’s life expectancy. Ranked the most impoverished zip code, 38126, residents have a life expectancy that is 13 years shorter than those living in the most affluent zip codes in the Shelby County. These impoverished, food desert zip codes, are majority African American and Hispanic as well.

The story of Memphis’s food deserts is a narrative that’s too common within the American system—all inequities are intersected, and to address them requires non conventional solutions. Taking steps in implementing non conventional solutions to mitigate Memphis’s food deserts can have broader economic and social benefits than just having an easier time getting to a grocery store. The food scarcity crisis is not a predicament that is easy to resolve. Ultimately, it is up to good ole fashioned local government to implement smart policy to tackle this. Hopefully this entails incentivizing the private sector and non profits to join the fight. The City isn’t the sole perpetrator in this, but it needs to lead the efforts in developing a more just food system in Memphis.

It’s the City’s responsibility

The most prevalent grocery store chain in Memphis is Kroger. The chain has closed two of their supermarkets in Orange Mound and South Memphis just three years ago. Many within these communities are now stuck finding means of transportation to get to the nearest grocer. Cars aren’t cheap, and Memphis’s car centric infrastructure and mediocre public transit system doesn’t make things better. The Guardian ran a feature that illuminated the issues with food insecurity in Memphis. A woman that’s filmed in the video shows that it takes her at least an hour and a half to get to a grocery store from her South Memphis home by MATA bus. That’s 3 hours round trip.

For those who do not want to make the long trek, corner stores and fast food restaurants are littered throughout Memphis, specifically in the most impoverished areas in the city, aka the food deserts.

Despite being the nation’s hunger capital, Memphis is consistently in the top 3 as the most obese cities in the country.

This title is simply achieved by the lack of access in fresh, healthy foods, and the over access of unhealthy food options. Shelby County is on par with the state and country when it comes to fast food options, but behind nationally in regards to grocery stores. The only reason Shelby County is ahead of the state in grocery store rates, is because of East Memphis and the suburbs. I think it’s also important to point out that TN is the 4th most obese state, with a much lower rate in available grocery stores than the national average. Shelby County has nothing to brag about when having a higher rate of supermarkets than the state average. It’s not nearly good enough. The correlation between obesity and the access to grocery stores is costing lives and taxpayers dollars.

After the Krogers shut down, members of the inflicted communities called for the City Council to conduct a Grocery Feasibility Study. The Council reluctantly approved the $18,000 study. The results yielded that one of the stores was earning a profit of a scant $30,000 a year, while the other was at a net loss of $275k a year. The study suggested that both areas were in need of a grocery store, but not a traditional one. A grocery that would be more feasible for the community, and could manage not running on high profit margins. The $174k prototype was rejected by the Council, and was ultimately the wrong decision.

The prototype grocery store proposed by the firm was not necessarily a new idea. It describes an operating paradigm similar to a food cooperative (food co-op). A food co-op is an outlet that distributes food and is structured as a cooperative, meaning the entity is neither public nor private. Moving forward, the City shouldn’t be hesitant to invest in food co-ops or any other community focused grocery stores. There is no better motivation tool for private actors and NGO’s/non profits, than investing in their sector.

Redlining is a thing and it is mentioned in the Guardian exposé.

The redlined areas are the lower income areas, which are the food deserts. It still baffles me that the plight of redlining — that started in the 30’s because of FDR’s National Housing Act — is still deeply entrenched in the fabric of cities. In this case, a lack of overall investment due to redlining and other frivolous zoning laws has resulted in the great commercial grocery store exodus in Memphis. We’ve even seen the iconic southern grocery chain Piggly Wiggly leave town. The chain’s origins are in Memphis. There are 530 locations that exist in 17 states, but not a single one in Memphis.

The City owes it to its citizens for its budgetary expenditures to reflect the needs of its community. Food co-ops and other unorthodox grocery models can be an alternative solution to supermarket woes in Memphis while addressing its attached socioeconomic needs. They’re worth investing in.

Understanding food cooperatives

Before we get deep into the potential impact of food cooperatives in Memphis, we must understand the main principles food co-ops are grounded in. Also, it needs to be clear that there is not a one size fits all approach in terms of operating a community grocery.

Food co-ops existed well before 2021. We can trace the concept’s history in the United States to at least 130 years ago. They became more prevalent in rural areas in the late 1800’s when farmers started adopting the practice of cooperatives. Co-ops hit their peak at the time during the Great Depression. Memphis even has a share of food co-op history. The Citizen’s Co-operative Society was established in 1919 by African Americans. The meat market co-op operated 5 storefronts and provided for over 75k Black Memphians.

It makes sense that cooperatives had salience at the time — whether it be economic or societal reasons. Historian and sociologist Anne Meis Knupfer argues in her book Food Co-Ops in America: Communities, Consumerism, and Economic Democracy, that there is an innate democratic impulse that exists within us. Meaning, the human instinct is to democratize food rather than commercializing it. It was only natural for folks to work as a collective to feed their communities when conventional free market capitalism fails to do so.

Food co-ops follow the 7 Rochdale Principles as a guideline on how to operate.

Voluntary and Open Membership

Democratic Member Control

Member Economic Participation

Autonomy and Independence

Education, Training, and Information

Cooperation among Co-ops

Concern for Community

These 7 guiding pillars are the bed rock of food co-ops and is what separates them from regular profit driven supermarket chains. Even though the principles are concrete and need to followed to run a truly successful and just food co-op, they provide a framework for a flexible, innovative system. Or multiple different types. The Urban Institute defined the different frameworks as follows:

Consumer Cooperatives

Membership is made up of people who want to buy goods or services from the cooperative; Membership is most often made up of community residents within geographic proximity to the cooperative business.

Farmer and Independent Small Business Cooperatives

These cooperatives serve members’ marketing, processing, and purchasing needs. Independent businesses in service sectors such as retail, hospitality, and agricultural businesses (which includes farming, fishing, and forestry) are the most typical sectors that form these sorts of cooperatives.

Worker Cooperatives

Worker cooperatives are businesses that some or all the employees own. Members produce and/or sell different goods and services and share profits.

Hybrid and Platform Cooperatives

These include two emerging models, consumer-worker cooperatives and cooperatives focused on workers in the freelance economy, which is often online or app based. In consumer-worker cooperatives, both the employee members and consumer members own and manage the cooperative.

Can food co-cps work in Memphis?

Manhattan transplant David Schrader of Next Step Global Farm Hand, understands the value food co ops can provide for impoverished zip codes. He specifically wants to open a food co-op in the Binghampton area, due to a Save-a-lot closing in the neighborhood last year. Schrader has made it explicit that to start up, he needs funding. Schrader is one of many who have attempted to start a food co-op in Memphis. Whether he’ll fail or succeed is to be determined, but if the City is serious about its food scarcity problem, it would simply invest in food co-ops like Jacob’s potential Binghampton operation. If the past serves as any indicator as if the City will support, the answer is no.

In 2004, Memphis’s most prominent food co-op, Midtown Food Co-Op closed its dorrs. Since then, no major food cooperatives have arisen in any of the food depleted neighborhoods in the City. South Memphis Farmers Market is about the closest model to a food co-op that has had sustainable success. During season (June-September), they host farmers markets where residents can directly purchase produce from local farmers. As an extension, they opened a year round grocery. This only took $1.2 million of funding that the City had no parts in contributing.

Others have tried the same model as South Memphis Farmers Market, searching high and low for grants and other funding. Unfortunately, not many that use a similar framework as South Memphis Farmers Market have failed because they weren’t sustainable.

There are two entities that use the community supported agriculture model within Memphis. The 275 Food Project sells subscriptions for seasonal produce packages that come to your door each week. Even though 275 offers Memphians a choice for quality groceries, their focus is more geared towards promoting local agriculture than serving Memphians in need. There’s no problem with this. Local farmers need support as well! But when the focus is more driven towards the producer/distributor than the consumer, CSA operations like these will be cater more towards affluent residents than those who are less fortunate. The Bring it Food Hub by Memphis Tilth is a nonprofit that uses a more innovative CSA model. Along with subscription packages, you also have the option of purchasing individual items, one time packages, and add ons to subscriptions. The Hub has an accessible online store where you can purchase all of these options.

Despite the lack of operational food cooperatives in the city, the Bring it Food Hub and South Memphis Farmers Market grocer make me optimistic that some variation of a food co-op or alternative grocery can work in Memphis. That’s with some push from public and private sources of course. Food co-ops have the potential to kill multiple birds with one stone. What makes the cooperative model uniquely sustainable is its economic empowerment threshold. Tackling unemployment is not enough in a majority Black city where nearly 3/4 of the city’s businesses are white owned.

The U.S. Census Bureau tabulated all businesses that have paid employees. It found that, in Memphis, 73.6% of those companies are owned by white people. A mere 6.4% of them are owned by Black people. In an overall metro with about the same number of white and Black people.

That means there are 11.5 times more white-owned businesses than Black-owned. Those white-owned firms made 46 times the revenue of Black-owned firms.

I’m more biased towards the food cooperative framework over CSA’s in Memphis (even though I’d fully advocate for more CSA’s and hybrid models) mainly because of the stat I just gave y’all. Community ran food co-ops promote economic gains turned generational/community wealth on a larger scale than CSA’s to me. Orange Mound, Frayser, and other communities like these need grocery stores that can employ neighborhood residents, promote Black ownership, alleviate hunger, and put reliance on corner stores and fast food in the rearview. Lastly, it can support local farmers and food producers, just like 275 and other CSA’s and farmers markets.

John Steinman’s Grocery Story: The Promise of Food Co-ops in the Age of Grocery Giants has a chapter specifically geared towards food co-ops as food desert remediation (he even mentions the Krogers that closed in Memphis). In this chapter, he outlines how some successful food co-ops in different cities have flourished. An example that struck me was Greensboro, NC due to the northeast quadrant of the city’s demographic similarities to Memphis’s poorest area code, 38126. The area had been a food desert since 1998 after a Winn Dixie shut down in northeast Greensboro. The long process of opening the Renaissance Community Co-op included plenty of crowdfunding and fighting with the City’s government.

A market research firm determined that that within a two mile radius of the proposed location, residents spent $1.34 million on groceries every week. If the co-op could capture 5 percent of this, the numbers added up confidently build a 10,530-square-foot grocery store.

It took $2.53 million to open the store. Funding came from many sources. In 2015, the co-op was awarded a $250k economic development grant from the City of Greensboro. Another $90k came in the form of grants from two local churches — one deeply rooted in the black community and a largely white church from the other side of town. More than $143k in loans came from the co-op’s 1,200+ member-owners. Each of those members also invested $100 into their member shares. Grassroots investor group Regenerative Finance secured over $250k in 0 percent loans from 29 investors. Other financial partners supporting the co-op’s launch included Fund for Democratic Communities, Cone Health Foundation, Community Foundation of Greater Greensboro, Shared Capital Cooperative, and The Working World. The co-op also relied upon the support of CDS — a network of food co-op consultants — and Uplift solutions, an organization supporting communities across the United States who are challenged with access to full-service grocery stores.

Renaissance Community Co-op opened in 2016 with 32 jobs filled by people living in the neighborhood.

Renaissance proved that it’s possible, but it most definitely takes a village. The City has nothing to lose by greasing the wheels and assisting community food co-ops with starting up, or even starting and playing part in operating one itself. If there is a concerted effort among community leaders, City government, outside forces, and the communities themselves, food co-ops as hunger mitigators can become a reality in Memphis.

Has the City done anything to address its hunger crisis?

Memphis 3.0 is the closest effort being made to undertake the food scarcity problem. The city describes it as:

The City’s comprehensive plan to guide land use, development, transportation, and other built environment considerations over the next 20 years. The comprehensive plan is essential to establish an ambitious vision of the future, but ensure clarity and predictability in growth and development patterns and how the City invests.

I must admit. Talking about Memphis 3.0 gets me giddy. I’ve personally been a fan since one of my professors introduced me to the plan a few semesters ago. It’s big, bold, targeted, fresh, and exactly what Memphis needs. But that doesn’t mean it’s perfect. Maybe one day I’ll write a blog post digging into the weeds of the plan to air all my gripes, but where it specifically lacks the most is in regards to hunger.

Memphis 3.0 is a community driven plan centered around uplifting dilapidated neighborhoods and maximize the more thriving areas in the City. “Anchors” are defined as “A place where people in the community gather to do things together.” The hope with focusing on anchors, is that they will create a ripple effect that positively impacts the neighborhood it’s in, surrounding anchors, and surrounding neighborhoods. Instead of a top to bottom approach, it’s a trickle up one, which is good. The City identifies three different types of anchors that are meant for specific areas based on the community’s economic situation.

Nurture- Nurturing actions provide stability in places that have experienced decline or where there is not sufficient market activity to drive change. Investments by the City and philanthropies will support incremental change to improve the lives of existing residents and promote additional future investment. Neighborhoods with low market demand or experiencing higher vacancy and disinvestment can be nurtured by catalytic public investments and incremental improvements.

Accelerate- Accelerating actions encourage nascent beneficial change that is underway, but which requires additional support to realize its full potential. A mix of investments by the City, philanthropies, and the private sector drive transformative change to realize the community’s vision for a place. Areas seeing real estate market investment and that have infill opportunities can be accelerated with public and private support.

Sustain- Sustaining actions support existing character. Infill development should improve the built form and enhance multi-modal transportation options. Investments primarily by the private sector will support steady market growth for community stability. Areas that are historic districts or areas that wish to see no change in form or development activity should be sustained with regulations that support current conditions.

By definition, the impoverished communities in need of quality food fall under the nurture anchor tree.

The anchor centric approach by prioritizing focus and direct investment into communities is the opposite of our typical austerity city planning. But there aren’t any grocery stores, or potential for them to be considered anchors in these areas that need “nurturing”. There are some strip malls in food deserts that contain restaurants and corner stores, but the plan should have a strategy to guarantee grocers will be explicitly given the title as anchors — whether they’re food co-ops, CSA’s, city ran grocers, or traditional supermarkets.

Communities are built on their access to necessities, and the ability for its residents to live good, prosperous lives. If the City can make it known how valuable grocery stores are, not only will communities be more eager to fight for easy access to quality food in their area, they will make sure the store won’t fail. We saw it in Greensboro, and seeing it in other cities. The community buy in will only be human nature —akin to Anne Meis Knupfer’s beliefs that it’s our natural desire to democratize.

The next step is ensuring that any Memphian can acquire quality food without jumping through all the hoops. The maps I’ve included provide a visual of how big and spread out Memphis is. Here’s a comparison that captures the enormous size of the City and the lack of mobility that exists within it. Memphis has a population similar to Boston’s of 600k+ residents. The difference is that Memphis is spread over 324 square miles, while Boston only 90. This means the City has a geographical problem. Memphis’s vast reach calls for a greater need for the MATA buses and other public transit options.

As shown above, the city planners have an ambitious goal to make Memphis’s transit system quicker (involving quick bus only lanes and other ideas). Notice the routes that the City is wanting to speed up. They’re located in our food deserts. Another point on the scoreboard for the city in their plan. If the recommended network can be achieved, it can be an immense help to those in food deserts. Development takes time, and public transit should be quickly improved to stop the bleeding of food scarcity. Along with the recommended MATA network, making Memphis more walkable — where anchors and “corridors” (strips of connected anchors) are short distances away from housing — should be a priority.

The Office of Comprehensive Planning (OCP) has stated multiple times that to maximize land use and promote sustainability, the City will build up and not out. Some of these plans to build up is providing more housing and stores through mixed use development. A lot of these sites will be anchors and corridors, where folks will be living in very close range to necessities and leisure activities. These mixed use anchors and corridors can play a part in quelling Memphis’s geographical flaws. But what can’t be neglected is including grocers in these projects.

Long story short, Memphis 3.0 has A LOT of potential and is a step in the right direction, but to truly address hunger in the city it needs to put making grocers community anchors on a pedestal, coupled with easy accessibility to these grocers. Investment in starting and sustaining groceries as anchors fits the criteria of “catalytic investment and incremental change”. Improving the City’s food system would have a tremendous return in its investment in the long run. Catalytic investment in groceries as anchors in all existing food deserts would promote incremental change turned sustainable growth. That’s if there’s a concentrated effort from City planners and lawmakers.

It’s big grocery’s fault too.

Memphis is not the only victim of Kroger shut downs. The country’s largest grocery chain has even closed its doors in poor communities in its own headquarter’s city, Cincinnati. It gets more cruel when you find out that Kroger made nearly $2.6 billion in profits last year, with $10 billion more in sales compared to 2019. In the middle of a pandemic! Plus, Kroger’s social media team has no qualms complaining about how tough it is to operate a grocery store on “razor-thin” margins.

Ken Klippenstein pointed out the fact they made over $2 billion in 2020. Kroger proceeded to delete the tweet and reemerge it without the added embarrassment.

Kroger’s lack of empathy for struggling communities is an all too familiar tale when it comes to commercial supermarkets and consumerism in general (that’s for another digression). As I mentioned before, one of the Krogers that closed in Memphis was making a yearly profit of $33k. Now imagine if Kroger shifted their business model for this store to cater more towards the community and sustain the tight profit margins they accrued. A food desert would be no more and neighborhood residents that lost their jobs would still (hopefully) be employed. Kroger could’ve utilized a CSA model, where excess and potentially wasted food from Krogers in more affluent areas in the 901 could serve well to hungry communities instead of in the trash. Similar to Walmart’s scaled down “neighborhood markets” (not here to give Walmart any credit) Kroger could have scaled down stores solely focused on providing fresh, essential foods. The Kroger could’ve voluntarily been the anchor for the Orange Mound neighborhood it left, providing jobs and quality foods to residents. Unfortunately, it’s neither a supermarket chain’s job to build up and provide for communities, nor is it their business model.

The commercialization of groceries is also to blame for Memphis’s food desert problem, and is the reason why Krogers close their doors when they aren’t reaching desired profit margins. Whole Foods, Sprouts, and Fresh Market have all made shopping for healthier options more expensive. None of these chains are located in areas that need their groceries anyway. They’re all located in more wealthy zip codes within the city.

After doing research on all supermarket chains in Memphis, I really couldn’t find many concrete things these corporations are doing to directly serve communities other than attempting to cut food waste and donating to organizations like Fighting Hunger. Even in their charitable efforts, there is no value of service and empowering those they are giving to. I’m not trying to knock any source of food charity, but at the end of the day if we actually want to fight hunger, we have to contribute to sustainable causes that build communities and promote sovereignty over their food system and health.

If Big Grocer can’t adopt a Grocery as a service model, then local chains will be of value in the conventional grocery store lane. One man in particular is working to help solve the problem is in this lane. Rick James owns Castle Retail group that operates the Cash Savers and High Point Grocery — three highly valuable groceries in less affluent areas. He is now planning on opening a grocery store in the 38126 zip code, the most impoverished in the city. James’s local grocery stores have been a success. The special sauce for his Cash Saver stores is that he runs a discount grocery business model that saves his customers cash (Kroger take notes).

He can’t do it alone. 324 square miles is a lot of space to fill with stores that provide quality foods to those who inhabit it. Instead of viewing the business venture of opening and operating a discount grocery store as a burden, Rick James is an example of it being the opposite. The grocery as a service paradigm is not only for co-ops, CSA’s, food banks, and famers markets, but it can also prosper under the more conventional grocery store model. There are 4 Cash Savers in the Memphis metro area and James is about to open his 6th overall store. He’s expanding. Not shutting down.

Again, as an optimist, things like these excite me. There truly isn’t a one size fits all approach to anything, and I’m glad there’s a Memphian that is demonstrating this when it comes to sustaining grocery stores in more impoverished areas.

Final Thoughts

We shouldn’t assume that food co-ops will automatically work out even though they offer plenty of promise. The Renaissance Community Co-op that I mentioned earlier didn’t have a happy ending. Steinman details their demise as one that included inadequate cash flow, low customer counts, and troubles with sustaining customers. A defaulted mortgage, reduced work staff, and eventual closed doors was the end result to their difficulties. Steinman points out that competing against conventional models are tough due to the lack of understanding when it comes to food co-ops. Additionally, food co-ops struggle with obtaining support from traditional banks.

All of the frameworks I’ve mentioned can very easily run into all of these problems in varying degrees. But there is a light at the end of the tunnel.

First off, food co-ops that have opened between 2008-2018 have a success rate of 75%. So believe it or not, Renaissance was in the minority. The reason for the success? The community engagement needed to run cooperatives. There are a lot of forces needed in terms of time, money, and service that seems like those who start food co-ops don’t want to let go.

Whether it’s food co-ops, CSA’s, or discount groceries, easy access to these stores will be paramount to Memphis’s local economy. Endeavors that bring in adequate revenue create economic momentum anyway, but the domino effect captured by successful groceries will be a bigger game changer than just about any other developments that the city views as important. The owner(s) of community supermarkets will inevitably benefit immediately (if successful). Depending on levels of investment and success, the community will capture the benefits of an accessible grocery store in the long run.

Meaning, success will directly incentivize the grocery store owners to do one of two things, or both. Owners will invest more money into expanding their services into other areas (queue Rick James) and/or encourage other city developers and communities to take on the risk and for the City to seriously consider the alt-grocery route.

Surrounding business in food deserts struggle due to lack of livability and purchasing power held by the residents it serves. Grocery stores are truly the anchors of communities. When a grocer is successful, there is a higher chance of businesses in close proximity to have success. Community grocers also have a greater ability to work directly with local producers. Overall, the local economy would be provided an enormous boost if food deserts were eliminated completely.

Communities with sufficient resources to obtain quality foods have lower rates in obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and many other illnesses. Memphians understand the severity of our obesity problem, as it’s been deemed as Memphis’s most significant health issue among other health disparities perpetuated by food deserts. Sustainable, alternative supermarkets can lengthen Memphians’ life expectancy and close the health gap between wealthy and poor residents in the city. Less Memphians could also rely on SNAP benefits and other welfare programs if the City simply worked on expanding its food safety net.

Ultimately, what I believe fits in a larger paradigm shift that’s needed. We’re starting to see it, but we need to advocate for a greater push. That is commercialization becoming more service oriented. I’m not here to crap on capitalism and markets, but different levers need to be pulled to make capitalism work for us, and not just the CEO’s and shareholders. Unfortunately, the markets cannot shift to this position alone. For Big Grocer to transition from being food focused to nutrition focused will take some poking from public players and and greater demands from the public.

The public sector is what sparks the economic match through fiscal and monetary policy on a macro scale. City planning is a driving force on a micro scale. Memphis has a job to do, and that’s toput its residents in the best position to thrive. Right now it’s not doing enough.

Time is ticking, and we’ll all be watching the City and its action or inaction on fighting hunger.